This is the Kodak Reflex, a genuine twin lens reflex camera manufactured by the Eastman Kodak Company from 1946 to 1948. It makes twelve 2 1/4" x 2 1/4" (6 x 6cm) images on 620 roll film. The Reflex was superseded by the Reflex II with minor changes from 1948-49.

Kodak isn't normally a company we associate with TLR cameras. Indeed this camera, and its successor the Reflex II, are the only true TLR cameras that Kodak ever manufactured. They also made pseudo-TLR cameras, such as the Brownie Reflex or Brownie Starflex, but these are simple box cameras with oversized reflective finders, not cameras with a focusing screen.

The modern twin lens reflex camera (a camera with two lenses, one used for focusing on a screen and one for taking the image) owes much of its origins to Franke & Heidecke in Germany, who developed the design we are familiar with today. Most twin lens reflex cameras following the Rolleiflex model take twelve 2 1/4" x 2 1/4" images, have one lens mounted above the other, and have a focusing screen that the user looks down into to focus and compose the image.

The basic design of the Rolleiflex was successful enough to spawn multiple copies from various manufacturers, ranging from cheap box camera lookalikes like the Brownies above, to serious competitors. In the USA, examples like the Argoflex E and Ansco Automatic Reflex provided domestic competition against the influx of German Imports.

The apparatus division at Eastman Kodak was watching the market for these cameras, but initially did not see it as lucrative enough to invest time and money into making something competitive. By the late 1930s, it was evident that the TLR was more than just a passing fad, and if Kodak wanted a piece of the market, they would need to make something to do it.

A 1939 internal Kodak document entitled Major Developments in New Apparatus details what Kodak had planned. The prototype camera, called 6 x 6cm Reflex Kodak and designated experimental number E-192, was a feature packed camera designed to beat the best of the German competition. It had a focal plane shutter, a split image rangefinder built into the viewing screen, automatic parallax correction, and a suite of interchangeable lens assemblies. But also, there would be an accessory light meter that would give the camera autoexposure capabilities.

The 6x6cm Reflex Kodak would never make it to market. Most likely, the immense R&D and projected sale costs were too high to justify building it. Also, the sudden entry of the United States into the Second World War and subsequent cease of civilian manufacturing disrupted consumer camera plans for Kodak.

After the war, when civilian manufacturing began again in earnest, Kodak began by continuing manufacture of pre-war camera designs. However, they also began new R&D work on camera designs that began releasing in 1946.

Among these was this camera, the Kodak Reflex, a much less ambitious version of a TLR that did see production and sales.

Let's take a look and see what they came up with.

The Reflex shares the same general layout as Franke & Heidecke developed for the Rolleiflex. Two lenses, one above the other, a top viewed focusing screen, and it makes twelve 2 1/4" x 2 1/4" images on 620 film.

620 was a film format developed by Kodak in 1932 to improve on the deficiencies of 120 film, which had outgrown its children's box camera origins, and by the 30s had began to be used in many more professional cameras. It uses the same width film stock as 120, but Kodak modified the spool to remove the rolled edge designed to prevent children from cutting their fingers, reduced the core and flange diameters to reduce size and material costs, and before its release, increased the number of images on a roll from six to eight. (120 film was, until the 1930s, supplied with only six 6 x 9cm images per roll). The increased film length would later be appended to 120 film, but it began on 620.

If you are are in need of 620 film, the good news is that a small supply of 620 spools and a darkroom/changing bag are all you need to use any modern emulsion available today in the 120 format. I recommend this method for transferring film, as it requires the least effort and actual touching of the film.

The Kodak Reflex weighs 2 lbs 1 oz (appx. 940 grams) and measures 5 3/4" x 3 3/4" x 4 1/8" (146 x 95 x 105mm) with the hood collapsed. Erecting the hood increases the height to 7 5/8" (194mm).

On the front of the camera we find the viewing lens, top and the taking lens, bottom. These are coupled by gear teeth on their perimeter which ensure the front elements of the lenses focus in unison and give the user a place to grip to focus. Using front element focusing was a price conscious decision, as it is much less costly to manufacture than something like the moving film plane of the Rolleiflex, but does not allow for the use of more highly corrected unit focusing lenses.

Somewhat unusually, the Kodak Reflex uses identical lenses in both positions. Some TLRs use a better lens for taking the photo, and a less complex and expensive one for viewing, but Kodak put in the effort to give you identical lenses for both, which means you should get the closest approximation to the actual photo as seen in the viewfinder.

You will find the cameras marked for either Anastigmat, Anastigmat Special or Anastar lenses, all 80mm f/3.5 and stop down to f/22. Don't be confused, these are all the same lens design, but Kodak changed their advertising vernacular over the years.

The lens design that falls under these designations is of uniform design. It is a four element lens of the Ernostar type. The Ernostar lens was developed as a very early fast lens by Ludwig Bertele in 1924 while he was working for Ernemann, and is notable for being the progenitor of the famous Zeiss Sonnar lens. The Ernostar lens uses four elements in four air spaced groups, and has no cemented surfaces.

The choice of this lens for this camera is unusual for Kodak, as they never used this lens design on any other consumer still camera. Kodak had a great deal of experience making Tessar and modified Tessar lens designs as well, so it wasn't a lack of options that prompted this decision. I have found no source that cites exact reasons for the Reflex using the Ernostar design, but my predominant theory is that the lack of cemented surfaces was cheaper to manufacture, and offset the cost of having two identical lenses on the camera.

Also unusual for the era, is that both lenses are hard coated, or in Kodak's terminology "Lumenized". It is typical to find either neither lens, or only the taking lens, coated on most TLRs. Very early examples had no lens coatings, but this was quickly adopted on production as the Ernostar lens suffers from reduced contrast, light transmission and flare due to its eight air-glass surfaces. Coated lenses can be identified by their Ⓛ marking on the lens barrel. For user cameras, coated lenses should be preferred.

The Flash Kodamatic shutter also offers flash synchronization for electronic flash, and both fast and medium peak flashbulbs. There is a lever on the underside of the lens and an adjustable control loosened by a screw above the cocking/release lever. For use with fast peak (5ms) flashbulbs, the screw is loosened and the letter F is revealed, for medium peak (15-20ms) bulbs, the same is true but the screw is slid over so that the letter M is revealed. In either case, once the shutter is cocked, you push the bottom lever over towards the cocking lever as far as it goes which sets the delay mechanism. If electronic flash is used, the delay lever is not used. This system seems a bit clunky, which owes to its origins as a self timer mechanism, repurposed for flash sync. Nonetheless, it does offer X, F and M sync.

On the left side of the camera we see a strap lug and the ASA bayonet flash connector, recessed into the body. There is also a 1/4" tripod socket (with a filler screw in place) and a locator hole. While this tripod socket could be used to mount the camera horizontally, its primary purpose is to mount the accessory flashgun for this camera.

The right side of the body is pretty sparse, we have the other strap lug and the film advance knob with its reminder insert. This insert rotates to align the mark on the knob with whichever Kodak film is loaded in the camera, giving you a reminder of what is loaded. It does not perform any mechanical function inside the camera.

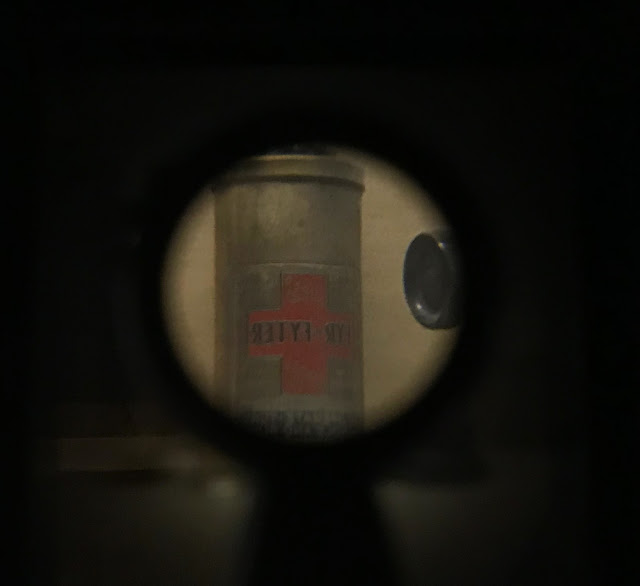

Under that we have the red window for film advance and its chrome lever which moves the light blind, so that the numbers on the backing paper can be read. This shutter is a nice feature, as it prevents sensitive films from being fogged by stray light that comes through the red window and bounces around past the backing paper.

The bottom of the camera has only the center mounted 1/4" tripod socket and four small chrome feet which steady the camera when it is sat on a flat surface.

The viewing hood is made of stamped sheet metal and has the Kodak name embossed in it. The top lens features a distance scale and depth of field scale for assistance in focusing.

Pressing the button on the back of the camera erects the focusing hood.

This allows you to view and focus on the screen. The focusing screen in the camera is plain old ground glass and not particularly bright. This cameras successor, the Reflex II, featured a Fresnel bright screen, the first TLR to do so.

There are no microprism focusing aids to help you focus on this screen, which can be challenging for most TLR cameras. The view you get on the screen is also reversed left to right, as with all top down viewing screen cameras. This may be disorienting for the novice TLR shooter, but is really not a problem once you are used to it.

Your one aid to focusing in this camera is a loupe which is mounted to the back of the hood and flips up into position when desired.

If using the ground glass and loupe is too slow a process for you, then the camera also has a solution for you. With the hood erected, the loupe and front panel can be flipped up. This in conjunction with an aperture in the back of the hood gives you a folding frame finder for quicker subject acquisition. This was recommended for use in photographing fast moving subjects like in sporting events, and as such is sometimes referred to as a "Sport Finder". Pre-focusing or zone focusing would be necessary when using the frame finder.

Now, features and specifications are all well and good, but how does the camera actually perform?

I re-spooled some Kodak Gold 200 on 620 spools and took this camera out for a trip. This was actually my first time using this film stock in medium format.

The above photo was the first on my roll and was a test to check for depth of field and out of focus rendering. It was shot with the lens wide open at f/3.5.

Focusing with the Reflex can at times be a challenge. I attempted to focus on the lettering of the tow truck, but ended up having the garage sign behind it in better focus than the truck. Now, I will caveat this by saying that I do have a mild form of astigmatism. It doesn't really affect my normal vision, but makes it more difficult to use focusing screens with no split image or microprism aid. Those with better eyesight may have an easier go of it.

Some of my images showed this artifact on the top of the frame. I initially thought this was due to a light leak, but after checking the camera, I am inclined to think it is more lens flare, as it doesn't occur on every frame and only inside the frame of the film, not on the edges. This is probably caused by having the sun in front of, or to the side of the lens, and bouncing around inside the lens. The coatings help, but aren't perfect. As a result, I would recommend the use of a lens hood (which I didn't have at the time of this shoot). A push on Kodak 1-1/2" / 38mm to Series VI adapter fits both lenses on this camera and allow the use of the whole suite of Kodak Series VI lens attachments, including filters, lens hoods and polarizers.

Despite being a capable camera, the Kodak Reflex did not stay on the market for a long time. It was available for only two years before being supplanted by the Reflex II, which had some minor styling changes, along with the addition of a Fresnel screen, a faster 1/300th top shutter speed and automatic frame counting. However, the Reflex II would be discontinued just a year later, giving this camera series a short run of three years from 1946-1949. After its discontinuation, Kodak would not manufacture another TLR camera ever again other than the aforementioned pseudo-TLR Brownies.

I could find no source to indicate why the Reflex was so short lived, or why Kodak never again attempted to make a TLR. Judging from the number of used cameras available on eBay and the like, the cameras certainly were selling, and they are by no means rare.

One contributing factor may have been cost. While the Reflex did not have the same feature set as a Rolleiflex, it was not an inexpensive camera. When introduced in 1946, the retail cost was about $120, by the time the Reflex II was released, the cost had risen to $155. In 1947, a Rolleiflex would cost you nearly double that of the Reflex II, but a more comparable Rolleicord II could be had for $165. Why buy the knockoff, when you could have the real thing for just $10 more I suppose.

Additionally, by the early 1950s, high quality and less expensive Japanese imported TLR cameras like the Yashicaflex were filtering into the United States, providing more competition in an already saturated market.

Nonetheless, the Kodak Reflex is certainly a high quality and capable camera, and in today's market can be had for bargain prices. This one cost me just $10 at a yard sale. Examples of the Reflex I can normally be found on eBay for less than $50 and of the Reflex II for less than $100, often in their fitted leather cases. If the focusing screen is seen as a detriment, replacements can be had with brighter Fresnel screens and microprism focusing aids.

My takeaway is this, if you want to get into TLR photography without paying much, but are willing to accept the tradeoff of re-spooling 620 film, then the Reflex is a great camera for the job.

Thanks for this thorough review of the Kodak Reflex. My Model II is one of my favorites. I also have a Mamiyaflex II which is a pretty close copy of Kodak's tlr. It makes sharp pictures too, though it lacks a bright screen.

ReplyDeleteAlso pleased to see the link to your blog from Photonet as I had somehow missed it before.